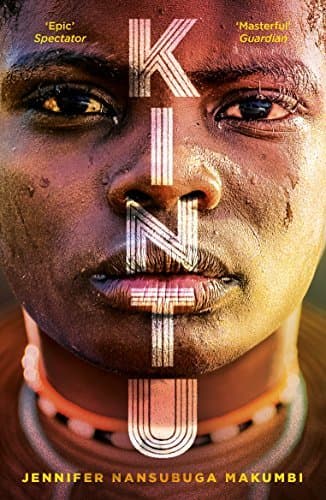

Kintu - Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

He was sacrificed at the altar of knowledge for knowing and refusing to know - Miisi's sister

**This review has some spoilers

Kintu is Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s first novel, published in 2014. With its premise being that of a cursed bloodline and generational curses, I went in sceptical, but 50 pages in, and I was fully sold, constantly wondering what would happen next.

The story begins in 1750 with Kintu Kidda, a governor in the Buganda Kingdom, on his way to pay homage to the new Kabaka. He has an entourage of his men and his adopted son, Kalema. Kalema was the son of a foreign Tutsi man, Ntwire. After the death of his mother during childbirth, Kalema was taken in by the Kintu family and raised together with the governor’s own son, Baale. His father, Ntwire, settled close by on a farm gifted to him by Kintu, keeping an eye on his son. Unlike Kalema, Ntwire refused to mesh with the Baganda people and insisted on his foreignness. In this homage journey, at Ntwire’s insistence, Kintu Kidda was taking Kalema to the palace with the hopes of him finding employment there.

Whilst resting at one of the stop points, Kalema is tending to Kintu’s needs, and due to a mishap, Kintu hits him with the intention of scolding, but instead hits his head, leading to the death of Kalema. Kintu is shocked by the incident, and once he arrives back in his province is too ashamed to declare the death of Kalema. Instead, he acts as though all went as planned and Kalema found employment. Ntwire, a man who had learned to rely on his senses to survive in a foreign land, suspects that something is wrong and goes in search of his son. But before leaving, he leaves a curse on Kintu. A curse that states that for Kintu and his people, to live will be to suffer and not even death would bring them relief.

This marks the beginning of the curse that would haunt the Kintu lineage. It starts and unravels with the death of his dear son Baale, followed by the suicidal death of his favoured wife Nnakato and soon after, Kintu Kidda himself would lose his own mind, flee his village and abandon his position as governor. What’s left behind is the curse that would manifest in the Kintu future generations as sudden death, madness and suicide and an instruction that is passed from generation to generation that no Kintu child should be hit on the head.

As for the family curse, Miisi argued that it was a documented fact that in Buganda mental health problems such as depression, schizophrenia, and psychosis ran not only in families but in clans—the so-called ebyekika, clan ailings. - Miisi

With this setting in place, we follow Kintu’s descendants and see the curse manifest in different ways. Finally, in 2004, the elders of the Kintu family decided to gather all the members of the family scattered across Uganda with the sole intention of breaking this generational curse. As we navigate through the family tree, we are left to wonder if indeed this generational curse can be removed and more importantly, if it exists at all.

“The thing is . . .” Suubi paused as if to think again, “You don’t realize that you’re cursed until you’re exposed to this other way of life. I mean, if we lived on our own, in our cursed world, we wouldn’t know. Then the curse would not exist.”

My view is that they came on earth, did their thing and now they have bowed out. Who is to say that things are not right? Nature is as ugly as it is beautiful. People drop dead, people kill each other, people go hungry: you don’t dwell, you just exist. But then this other world comes along and gives you ideas. You start to think, hmm, I am not right, it’s not fair. Things you would never have said before. Soon you start to blame everything on a curse.”

“Our own cursed world!” Nnabaale laughed belatedly. “It’s just hit me.” “What is a curse to some people is normal to others.

- Suubi

Kintu, the book, shows Uganda in a new, interesting light, touching on quite a number of themes from colonisation, religion & spirituality and more importantly, mental health and how it manifests in African societies. Is it possible for us to break generational curses? How much of it is true, and how much is a coincidence?

Africans are greatly spiritual and believe in cycles, curses, blessings and the synchronicity of everything. This then leaves us grappling with questions such as how much of a death, an illness, a misfortune is just that or can it be traced to agreements that our ancestors made decades ago? How much of our free will is actually ours, and can we defy our 'fate'? Or for the more rational, are we stuck in a loop of self-fulfilling prophecies due to our beliefs? Jennifer Makumbi explores all these possibilities in this book.

My reviews of Makumbi’s books always fall short. Her stories carry me beyond the realm of reality, where I forget to think critically and analyse the plot or the characters. This usually leaves me with a feeling that cannot be put into words. The feeling Kintu left me with was a feeling of being seen and understood. The story is set in Uganda, and as a Kenyan, I still feel a sense of familiarity with the characters, their traits, and plights; a feeling that is hard to come by.